This is the ultimate showdown of ultimate destiny

Good guys, bad guys, and explosions as far as the eye can see

And only one will survive, I wonder who it will be

This is the ultimate showdown of ultimate destiny

-Lemon Demon

Before Walt Bismarck was inspiring Disney to train a Predator drone on him for making racist parody meme videos out of wholesome 90s movies, before Twitter turned into X and endless doomscrolling, in fact before there was Facebook or Twitter or 4chan at all to rot our brains - let alone Tiktok or Instagram, there were very early viral image sensations - mostly, due to an animation language initially called Shockwave but soon to be subsumed into Flash. And you very likely did not escape the badgers.

Back in the days before Y2K memes consisted of things like the Dancing Baby.

“Games Portals” were common, especially within the larger “portal” concept - Yahoo had a number of Flash games, as did MSN, and there were smaller groups like PopCap - who hit it big with a game that we probably all remember. (It’s still surprisingly good - and the sequels… less so.)

For that matter, PopCap was also behind Bejeweled, which was one of the first big Match Three games.

Independently, Armor Games and Kongregate in 2004 and 2006 took a run at the Flash Games portal concept. Before that, Shockwave.com was around in 1998: AddictingGames.com spun off from there in 2002 and hosted the first of the Bloons Tower Defense games. Games studio Ninja Kiwi has survived and adapted and I still play - as now do my kids! - derivatives of this game to this day.

The rise of viral websites is a fascinating chapter in internet history, reflecting the evolution of technology, user behavior, and digital culture from the late 1990s through the early 2010s. These sites—think eBaum's World and Newgrounds, or trollier stuff like YTMND and SomethingAwful, which birthed 4Chan and others—captured the zeitgeist of an internet transitioning from niche hobby to mainstream phenomenon. Newgrounds may have been among the most famous and long-lived, but they are lodged in the brains of those of us who grew up terminally online. Here’s how they emerged, peaked, and shaped the online landscape.

Pre-Viral Foundations and the Webring Era (Late 1990s)

The groundwork for viral websites was laid in the mid-to-late 1990s with the spread of accessible web tools:

Tech Enablers: HTML and Macromedia Flash (debuted 1996) let amateurs create animations and games without heavy coding knowledge. Dial-up modems, while slow, connected millions to the web—by 1998, 41% of U.S. households were online (Pew Research). Early streaming technologies like RealPlayer let people listen to media online though the inevitable “Buffering…” message was a good indication you were about to have a choppy connection.

Early Hubs: Sites like GeoCities (1994) and Angelfire hosted personal pages with quirky content—dancing baby GIFs, MIDI music, guestbooks. Bulletin boards (e.g., Usenet) and AOL chatrooms spread links via word-of-mouth, and users linked to similar content with “web rings” based on themes and shared interests - sport teams, musicians or music genres, games, books, anime, collectables, hobbies, and the like.

Cultural Shift: The internet was a Wild West, unpolished and experimental. Users craved quick, shareable distractions—humor, shock, or novelty—over static info pages. People began trolling one another with the infamous Goatse shock image - no, I’m not going to link it, do yourself a favor and don’t look it up - in 1999.

This set the stage for sites that could hook users and spread fast.

The Flash Boom and Early Viral Sites (1999–2004)

Flash’s rise turbocharged the viral web. Its lightweight, browser-based format suited slow connections, and its interactivity beat static GIFs or text. Enter the first wave of viral sites:

Newgrounds (1999): Tom Fulp’s platform exploded with Pico’s School and user submissions. Its open Portal system made sharing inevitable—users emailed links, instant-messaged them, or posted them on forums.

Albino Blacksheep (1999): Focused on animations like “The End of the World,” it thrived on absurdist humor that begged to be forwarded. Many ICQ messages in the day had links to Albino Blacksheep craziness.

Homestar Runner (2000): The Brothers Chaps’ cartoon series spread via email chains, with catchphrases like “TROGDOR!” and the ramblings of Strong Bad becoming insider memes.

eBaum’s World (2001): Aggregated audio, pics, and (largely stolen) Flash content, banking on volume over originality. Its soundboards went viral via AIM and MySpace shares.

Why They Worked: Bandwidth was precious, so short, punchy content (30-second clips, 1-minute games) ruled. Social media didn’t exist—virality relied on email forwards, instant messaging, and forum posts (e.g., Something Awful, 4chan’s predecessor). A 2001 Nielsen study pegged average daily internet use at 30 minutes—users wanted instant gratification.

Peak Virality, Aggregation, and Meme Machines (2005–2009)

By the mid-2000s, broadband surged (56% of U.S. homes by 2006, FCC data), unlocking video and bigger files. This era birthed iconic viral sites and a meme-driven culture:

YTMND (2004): Max Goldberg’s “You’re the Man Now, Dog” turned a Sean Connery clip into a customizable meme generator. Simple loops—like “Picard Song” or “lol, internet”—spread via Digg and LiveJournal.

4chan (2003): Launched by moot (Chris Poole), it became a meme factory with /b/’s random chaos. Rickrolling (2007) and LOLcats (via I Can Has Cheezburger, 2007) trace back here. 4chan rapidly went downhill into absolute madness and trolling depravity, which may be why it is so

welldistinctly remembered. (I briefly worked for a company called Fourgen, and literally every time I tell someone that they mishear me as “you worked for 4Chan?!” - no, they were a boring supply chain management software firm.)FunnyJunk (2001): A quieter player, it grew into a meme aggregator, peaking with user uploads in the late 2000s.

Million Dollar Homepage (2005): a 1000x1000 pixel page, sold off pixel-by-pixel to advertisers, this seemingly inane concept in fact caught mimetic fire and made its creator slightly more than a million dollars before taxes as well as making him Internet famous; somewhat hilariously, Alex Tew raised this money to fund his business degree and then dropped out after a semester.

YouTube (2005): The game-changer. Early hits like “Numa Numa” (2004, pre-YouTube, revived there) and “Charlie Bit My Finger” (2007) showed video’s viral power. It pulled traffic from Flash sites but also amplified them via embeds. YouTube successfully went mainstream by being acquired by Google; they grew faster than Google Video thanks significantly to seeding their video growth with video content that they could plausibly yoink back off when DMCA requests came in, but it gave them viral growth that outstripped everything else other than the peer-to-peer services that Hollywood was busy playing whack-a-mole with (Napster, Kazaa, Limewire, Scour, Bittorrent, etc). And a lot of the memes that had originally existed as Flash content were converted into YouTube content - either directly as Flash videos to YouTube videos or for instance, the Potter Puppet Pals went “live-action” puppets rather than Flash, here is the famous/infamous Mysterious Ticking Noise.

Mechanics of Spread: Social bookmarking (Digg, StumbleUpon) and proto-social platforms (MySpace, early Facebook) accelerated sharing. A 2008 study by HP Labs found 20% of YouTube views came from viral chains. Sites leaned on shock (eBaum’s gore clips) or Encyclopedia Dramatica’s catalog of Everything Offensive, humor (Homestar’s whimsy), or interactivity (YTMND’s remixes) to hook users.

The Golden Age of Aggregation (2009–2012)

As smartphones and social media matured, viral sites pivoted to curation:

eBaum’s World: Post-2007 sale, it doubled down on user submissions and safer humor, hitting 1.2 million daily uniques in 2010 (Comscore).

The Chive (2008): Marketed “probably the best site in the world,” it curated photos and GIFs for a frat-bro vibe, rivaling eBaum’s.

9gag (2008): A Hong Kong-based meme mill, it streamlined 4chan’s chaos into scrollable laughs, peaking with millions of daily users by 2012.

BuzzFeed (2006): Originally a viral lab, it hit stride with listicles and quizzes by 2011, mastering Facebook’s algorithm.

Shift in Dynamics: Twitter (2006) and Facebook’s News Feed (2009) replaced email forwards. Mobile browsing (iPhone launched 2007) demanded fast-loading content. Viral sites either adapted (YouTube’s mobile app) or clung to desktop nostalgia (Newgrounds).

Decline and Transformation (2013–2020)

The 2010s saw viral sites wane as platforms took over:

Tech Disruption: Flash’s death knell (Adobe’s 2017 sunset, ended 2020) hurt sites like Newgrounds, though HTML5 saved some (e.g., Friday Night Funkin’). Mobile apps outpaced browser games.

Platform Dominance: Instagram (2010), Vine (2013), and TikTok (2016) redefined virality with short-form video. YouTube’s algorithm favored creators over aggregators.

Cultural Fatigue: Users grew savvy to recycled content. eBaum’s plagiarism scandals and 9gag’s repost-heavy feed lost goodwill.

Many sites faded (YTMND shut in 2019), sold out (eBaum’s to Literally Media), or niched down (Newgrounds as indie haven). BuzzFeed pivoted to news, then faltered; The Chive chugged along quietly.

Retrospective

As I write this, the viral website era feels like ancient history, but its DNA lives on:

Influence: TikTok’s 15-second dopamine hits echo YTMND’s loops. Twitch streams owe a debt to Flash games’ interactivity. Memes—born on 4chan, refined on 9gag—rule discourse and arguably influence modern elections.

Survivors: Newgrounds thrives as a creative archive, eBaum’s limps as a nostalgia play, and YouTube remains a juggernaut, though significantly because Google/Alphabet gave it the clout it could never have survived without on its own. And who knows, perhaps 4chan can be said to have given us President Trump at least in 2016.

Lessons: Virality taught the web speed and shareability matter. Early sites proved small teams could rival giants—until giants (Google, Meta) co-opted the model. And every now and again they bring a new challenger to the table, though more frequently these days as an app rather than a website.

The rise of viral websites was a fleeting, messy explosion of creativity and opportunism, fueled by tech leaps and a pre-algorithm internet. They were the web’s adolescence—wild, unrefined, and unforgettable.

Let’s look a little more at some of the particularly influential players from back then - especially ones that you might still be able to look at these days.

Newgrounds

Newgrounds traces its roots to 1991, when Tom Fulp, a teenager from Perkasie, Pennsylvania, started creating content under the name "New Ground" for a school zine called The Lillypoopian Gazette. This early creative outlet laid the groundwork for his later projects. In 1995, at age 17, Fulp launched the first iteration of Newgrounds as a Neo Geo fan site hosted on AOL. Named "New Ground Remix," it was a simple page showcasing his artwork and reviews of Neo Geo games—a niche console he adored. This was a time when the internet was still young, and personal sites were often passion-driven experiments.

By 1998, Fulp had shifted gears. He registered newgrounds.com and relaunched it as a hub for his own games and animations, inspired by the rise of Macromedia Flash (later Adobe Flash). The turning point came in 1999 with two releases:

Club a Seal: A darkly humorous game where players whacked seals, reflecting the edgy, unpolished vibe that would define Newgrounds.

Pico’s School: Released shortly after the Columbine shooting, this controversial game featured Pico, a redheaded kid fighting off a school invasion. Its raw style and shock value drew attention, cementing Newgrounds as a platform unafraid to push boundaries.

Around this time, Fulp introduced the "Portal," an automated submission system allowing anyone to upload Flash content. This openness—combined with a voting system where users rated submissions—created a chaotic, creative ecosystem. It was a stark contrast to curated sites, giving rise to the tagline "The problems of the future, today!"

The early 2000s were Newgrounds’ golden age. The site exploded in popularity as Flash became the internet’s go-to tool for animation and games. Key milestones:

2000: Fulp released Alien Hominid, a side-scrolling shooter co-developed with Dan Paladin. Its success on Newgrounds led to a console port in 2004 (GameCube, PS2), proving the platform could launch real careers.

Community Growth: Creators like Adam Phillips (Bitey of Brackenwood), David Firth (Salad Fingers), and James Farr (Xombie) found a home on Newgrounds, alongside countless amateurs. The site’s forums buzzed with collaboration and feedback.

NG BBS and Culture: The Bulletin Board System (BBS) became a chaotic social hub, fostering memes like "Bedn" (a user who photoshoped himself into fame) and rivalries with sites like SomethingAwful.

Traffic soared—by 2002, Newgrounds was one of the web’s top destinations, often crashing from bandwidth overload. Fulp ran it solo initially, funding it with ads and his own pocket, until his brother Josh joined as a programmer in 2004.

As Flash matured, so did Newgrounds:

In 2006, the site got a major redesign, introducing the red-and-black aesthetic still in use today. Features like the Audio Portal (for music submissions) launched, birthing hits like Geometry Dash’s soundtrack. Pico Day is an annual event starting in 2006, which celebrated the mascot Pico with fan-made content, reinforcing community spirit. And some time around then, there was a monetization push: Fulp experimented with ads and partnerships (e.g., with Mochi Media) to support creators, though revenue was always tight.

Meanwhile, Castle Crashers (2008), another Fulp-Pladin collab, started as a Newgrounds prototype before becoming a smash hit on Xbox Live Arcade. This era solidified Newgrounds as a talent incubator.

The 2010s brought challenges. Apple’s rejection of Flash on iOS (2010) and the rise of HTML5 signaled the tech’s decline. Newgrounds felt the pinch. Casual gamers shifted to mobile apps and YouTube, causing a traffic dip. Then, In 2017, Adobe announced Flash’s end-of-life by 2020, forcing a reckoning.

Fulp didn’t sit still. He embraced HTML5 early, launching the Newgrounds Player (a Flash emulator) in 2019 and encouraging creators to adapt. The site also leaned into its archival role, preserving decades of content. Events like Flash Jam 2020 celebrated the old tech while pushing new tools.

Newgrounds wasn’t entirely about games - just significantly so - but it’s fair to say that they wouldn’t really have “made it” without flash games. Newgrounds has hosted thousands of games over the years, many of which became cult classics or launched broader legacies. But there are a few that really stand out.

Pico’s School (1999), made by Tom Fulp, is a point-and-click action game where Pico, a spiky-haired kid, fights off a gothic gang invading his school with weapons like guns and scissors. Released shortly after Columbine, its dark humor and edgy tone sparked controversy but also drew a huge audience. Pico became Newgrounds’ unofficial mascot, inspiring fan games, art, and Pico Day. It showcased Flash’s potential for narrative-driven games and cemented the site’s reputation for … let’s say… unfiltered content. Eventually, spinoffs like Pico vs. Uberkids and Pico’s Unloaded followed, and Pico remains a symbol of Newgrounds’ early days.

Alien Hominid (2002), made by Tom Fulp and Dan Paladin (Synj), is a fast-paced side-scroller where a crash-landed alien blasts through FBI agents with cartoonish violence. Its hand-drawn art and tight controls stood out among simpler Flash fare. One of Newgrounds’ first breakout hits, it racked up millions of plays and won awards like the 2002 “Game of the Year” from NG users. Its success led to a full console release in 2004 (PS2, GameCube) by The Behemoth, Fulp and Paladin’s studio. This proved Newgrounds could be a launchpad for commercial success and got people to take this site seriously.

Madness Combat (2002), made by Matt Jolly (Krinkels). Originally an animation, it spawned Madness Interactive, a sandbox shooter where players control a faceless grunt in a bloody, minimalist world. You could customize weapons and wreak havoc in a physics-driven chaos. The game’s simplicity and gore tapped into Newgrounds’ love for visceral, no-holds-barred entertainment. It birthed a massive fanbase and countless tributes. The Madness series grew into a franchise, with annual Madness Day events and a 2021 Steam release (Madness: Project Nexus). Krinkels remains a Newgrounds icon. Personally I hated this game, but there were a lot of people who seemed absolutely enthralled with it.

The Last Stand (2007) by Chris Condon (ConArtist) was a zombie survival game (in an era where zombies were remarkably popular) where you fortify a barricade, scavenge for weapons, and fend off waves of undead. Its moody atmosphere and resource management hooked players; a combination of strategy and action, it became one of Newgrounds’ most replayed titles. Its polish showed Flash’s growing sophistication. It spawned several sequels (The Last Stand 2, Union City, Dead Zone), with Dead Zone evolving into a multiplayer game. ConArtist later took his talents to bigger projects.

Super Meat Boy (2008) by Edmund McMillen and Tommy Refenes (Team Meat): this punishing platformer has you guide a squishy cube of meat through buzzsaws and spikes to save Bandage Girl. The Newgrounds version was a prototype with brutal difficulty and retro charm. A viral sensation on Newgrounds, it showcased McMillen’s knack for twisted, addictive design (he’d later make The Binding of Isaac). Its popularity demanded a full release. Expanded into Super Meat Boy (2010) on Steam and consoles, becoming an indie darling. Newgrounds was its proving ground. This isn’t really my cup of tea either; but this game and especially its pseudo-successor The Binding of Isaac is one that one that seems endlessly popular amongst people I know.

Crush the Castle (2009) by Joey Betz and Chris Condon, this physics-based game where you launch trebuchet projectiles to topple castles and kill royalty. Simple yet satisfying, it leaned on destructible environments. You may have played this one, but if you didn’t you almost certainly know its successor because it directly influenced Angry Birds (Rovio cited it as inspiration), showing Newgrounds’ ripple effect on mobile gaming.

Friday Night Funkin’ (2020) by Ninjamuffin99 (Cameron Taylor), PhantomArcade, Kawai Sprite, and Evilsk8r - a rhythm game where Boyfriend battles foes (like Daddy Dearest) in musical showdowns to impress Girlfriend. Its funky art, catchy tunes, and Dance Dance Revolution-style gameplay exploded in popularity. This was a late-Flash/early-HTML5 phenomenon, it hit Newgrounds during the 2020 Flash sunset and became a cultural juggernaut. Its open-source nature fueled mods and fan content. It revived Newgrounds’ relevance, with a Kickstarter for a full version raising over $2 million. It’s a bridge between the site’s past and present.

These titles reflect Newgrounds’ ethos: raw creativity, accessibility, and community. Early games like Pico’s School thrived on shock and simplicity, mid-era hits like The Last Stand showed polish, and modern ones like Friday Night Funkin’ adapted to new tech while keeping the site’s spirit alive. They range from amateur passion projects to seeds of million-dollar franchises, all shaped by Newgrounds’ anything-goes platform.

But more than anything I remember Newgrounds for this meme.

Newgrounds - perhaps for historical (or hysterical) reasons - still has this link. If you prefer it from YouTube, it’s here.

As if to prove that this meme would never die, 2016 brought it back, though it wasn’t the hit it was back in the way - I saw this one linked from Tom Kratman.

As I write this, Newgrounds remains a niche but vibrant platform:

Post-Flash: It fully supports HTML5, WebGL, and other modern formats, hosting games like Friday Night Funkin’ (2020), which exploded in popularity and echoed the site’s early chaotic energy.

Supporter Model: A Patreon-style subscription system lets users fund the site and unlock perks, keeping it ad-light and independent.

Legacy: With over 25 years of history, Newgrounds is a digital time capsule. Its unfiltered spirit endures, even as it competes with polished giants like Steam or itch.io.

It can be reasonably said that Newgrounds shaped internet culture by democratizing creativity. It launched careers (e.g., Matt Jolly of Angry Birds fame), inspired YouTube animators, and pioneered user-generated content models later seen in Roblox or TikTok. Its irreverent tone—think Madness Combat or Tankmen—set it apart from sanitized alternatives.

Tom Fulp, still at the helm, has kept it a labor of love. In a 2021 interview, he reflected, “Newgrounds was always about giving people a voice, even if it’s messy.” That messiness, paired with resilience, is why it’s still kicking in 2025.

ebaumsworld

eBaum's World is an entertainment website that carved out a notorious niche in the early internet landscape, known for its mix of humor, viral content, and a reputation for controversy. Here’s a rundown of its history, from its inception to its current state.

eBaum's World was founded in 2001 by Eric "eBaum" Bauman, then a 21-year-old from Rochester, New York, with help from his father, Neil Bauman. Initially, it was a simple site focused on sharing funny audio clips, pictures, and prank call "soundboards" modeled after the Jerky Boys - interactive tools letting users play celebrity quotes. The site’s name was a playful nod to Eric’s nickname, blending it with a Wayne’s World vibe. Launched during the dot-com bubble’s aftermath, it tapped into the growing appetite for quick, irreverent online entertainment, competing with early players like Newgrounds and Albino Blacksheep. By 2003, it was pulling in significant traffic, thanks to its unfiltered humor and user-friendly interface, though it was already drawing ire for reposting content without credit.

The mid-2000s marked eBaum's World’s peak - its rise to fame/infamy, and its descent into controversy. It became a go-to hub for viral videos, Flash animations, and memes, boasting over a million daily hits and ranking among Alexa’s top 500 sites. Features like the "Moron Mail" feedback section and a merchandise store added to its quirky appeal. However, its growth came with a catch: much of its content was lifted from other sites—Newgrounds, Something Awful, YTMND, 4chan, and Albino Blacksheep—often watermarked with the eBaum’s logo, implying ownership. This sparked feuds:

2005: Something Awful accused eBaum’s of stealing Photoshop Phriday images, leading to watermark wars.

2006: A YTMND animation, "Lindsay Lohan Doesn’t Change Facial Expressions," was reposted without credit, igniting a flame war. YTMND users retaliated with spam and DDoS attacks, prompting Neil Bauman to call it "cyber-terrorism." A truce was reached when Max Goldberg (YTMND’s founder) and the Baumans agreed to remove offending content, though tensions lingered.

Albino Blacksheep Clash: The theft of "Animator vs. Animation" led creator Alan Becker to threaten legal action. Bauman paid $250 and coerced an apology from Becker, only to remove the animation later under pressure.

Corporations like Viacom and Sega also threatened lawsuits over copyrighted material, such as GI Joe parodies and hot-linked games. eBaum’s defended itself by claiming user submissions came with consent forms, but its reputation as a content thief was sealed.

In August 2007, Eric sold eBaum's World to HandHeld Entertainment (later ZVUE Corporation) for $15 million upfront, with $2.5 million in stock and a promise of $12.5 million more over three years. Bauman stayed on as an employee, and the site briefly flirted with TV ambitions—a 2006 Fox pilot hosted by Chris Jericho fizzled out. By 2009, ZVUE fired Bauman and much of the original staff, a move he called a betrayal in a blog post. He vowed a comeback with "eBaum TV," but it never materialized beyond a Twitter presence with sparse updates and a dead-end "eBaum’s Nation" tease. The site’s community, already soured by its past, didn’t rally behind him.

Under ZVUE, eBaum's World pivoted to legitimacy. It partnered with ABC-Disney in 2012 for Right This Minute, a viral clip show, and G4’s Web Soup in 2011 for "This Week in Fail," both modestly successful. ZVUE relocated to San Francisco, but by 2016, it sold eBaum’s to Literally Media, an Israel-based company owning Cheezburger, Know Your Meme, and Cracked. Literally Media shifted the site to a user-submitted model, paying contributors via an "eBones" points system tied to ad revenue. The raw edge dulled—nudity vanished from its "adult" section, and content leaned safer, often echoing sites like The Chive.

As I write this, eBaum's World persists, but as a shadow of its former self. It’s still active, hosting memes, videos, and photos, but lacks the cultural clout of its heyday. The Literally Media era has kept it afloat with a cleaner image, though critics argue it’s a sanitized relic, recycling trends rather than setting them. The forums, once a rowdy hub, shut down in 2019, and Bauman’s sbaumsworld.com (a post-firing spinoff) faded into obscurity. Nostalgia keeps it relevant for some—Reddit threads recall its wild early days—but it’s no longer a trailblazer.

eBaum's World was a pioneer of viral culture, predating YouTube and 9gag, but its legacy is bittersweet. It amplified internet humor and user-generated content, yet its plagiarism scandals left a stain, fueling rivalries that shaped early web communities. Its rise and fall mirror the internet’s shift from chaotic frontier to corporate playground. Eric Bauman, once a slacker-turned-millionaire, vanished from the spotlight, leaving eBaum’s as a cautionary tale of fame built on borrowed foundations.

Albinoblacksheep.com

Albino Blacksheep (often abbreviated ABS) is an animation and media-sharing website that carved out its own niche in early internet culture. Albino Blacksheep was founded on January 4, 1999, by Steven Lerner, a student at the University of British Columbia in Toronto, Canada. It started as a personal project to promote his band, also called Albino Blacksheep, which he’d formed in 1996. In 2000, Lerner took a web design course and revamped the site into a personal multimedia blog. This version featured rants, graphical images, and a live video stream from his webcam—pretty cutting-edge for the dial-up era. By 2001, he shifted gears again, opening it up for user submissions. Now it hosted images, animations, music, and text files, with a focus on Adobe Flash content. This pivot turned ABS into a community-driven platform, tapping into the growing popularity of Flash as a creative tool.

ABS hit its stride in the early 2000s as a hub for Flash animations, games, and quirky media. It became a go-to spot for independent creators to share offbeat humor and experimental works. Memes like “Peanut Butter Jelly Time” (a dancing banana set to a catchy tune), “The End of the World” (a darkly funny apocalypse skit), and “The Ultimate Showdown of Ultimate Destiny” (an epic cartoon battle royale, and also the picture at the top of this page - seriously, if you haven’t seen this song/meme, it’s crazy - click through for the YouTube remaster) exploded from ABS, racking up millions of views across the web. The site’s peak came around 2006, with about 1.5 million daily pageviews, rivaling platforms like Newgrounds for Flash dominance. Lerner even pulled off a notable Google bomb in 2003, rigging “French military victories” to redirect to a snarky ABS page—a classic internet prank.

ABS fostered a tight-knit community via forums and chat rooms where users traded ideas and remixed content. It hosted early animutation—a bizarre Flash style pioneered by Neil Cicierega (think “Hyakugojyuuichi!!!”)—and helped bands like Tally Hall gain traction with videos like “Banana Man.” The site’s ethos was DIY and irreverent, a stark contrast to the polished web of today. Annual events like the Tournament of Flash Artists (TOFA) drew global animators for cash prizes, boosting its cred among creators.

The rise of YouTube in 2005 shifted the landscape. ABS joined YouTube early as a partner channel, cross-posting hits like “Peanut Butter Jelly Time” (nearly 23 million views there), but it couldn’t keep pace with video’s dominance. Flash’s decline—culminating in Adobe’s 2020 phase-out—hit hard. Search interest in ABS tanked after 2010, though it stayed alive. Lerner adapted by adding HTML5 support, keeping the site functional as a nostalgia hub and a space for new, non-Flash content.

Even today, Albino Blacksheep endures under Lerner’s stewardship from Toronto. It’s a shadow of its former self—traffic’s a fraction of its peak—but it still posts fresh media, from animations to games, and engages via social platforms like YouTube and Reddit Toronto (though less so lately). The site’s design remains simple: a navigation bar for categories like “Animations” and “Games,” a banner showcasing featured works, and sections for top and recent uploads. It’s a living archive of internet classics, revisited by aging geeks and curious zoomers alike.

Albino Blacksheep helped shape early web culture, bridging the gap between static pages and interactive media. It’s less infamous than 4chan but just as pivotal for memes and DIY creativity. Critics certainly call it a relic, overtaken by slicker platforms, yet its survival speaks to a loyal core and a refusal to fully gentrify. It’s the internet’s quirky uncle—still kicking, and definitely still weird.

4chan

4chan is an anonymous imageboard website founded in 2003 by Christopher Poole, known as "moot." It’s a chaotic, unfiltered corner of the internet where users post anonymously under boards categorized by topics like /b/ (random), /pol/ (politically incorrect), /a/ (anime), and /v/ (video games). The site’s lack of registration and minimal moderation fosters a raw, free-for-all culture—think of it as a digital Wild West. Posts are ephemeral; threads get pruned as new ones push them off the board.

It’s infamous for its role in internet subculture, birthing memes like Rickrolling, lolcats, and Pepe the Frog. It’s also tied to hacktivist groups like Anonymous, which emerged from /b/ in the mid-2000s, launching stunts like Project Chanology against Scientology. But it’s a double-edged sword—while it’s a creative hotbed, it’s also a cesspool for trolls, edgelords, and extremist content, especially on boards like /pol/, which has been linked to conspiracy theories like QAnon and the rise (and fall) of the alt-right back 2014-2016.

Internet meme culture is a sprawling, ever-evolving beast, and 4chan’s fingerprints are all over its DNA. Memes are the internet’s shorthand—images, videos, phrases, or ideas that spread virally, often remixed with humor, irony, or absurdity. They’re a language of their own, shaped by platforms, subcultures, and the collective mood of the moment.

4chan kicked things off in a big way. Back in the mid-2000s, /b/—the "random" board—was a meme factory. Take Rickrolling: in 2007, users started baiting people with fake links to Rick Astley’s “Never Gonna Give You Up” video. It was peak troll energy and spread like wildfire. Then there’s lolcats—those goofy cat pics with broken English captions (“I can has cheezburger?”)—which trace back to 4chan’s /b/ before spinning off into sites like I Can Has Cheezburger. Pepe the Frog, a chill cartoon frog from Matt Furie’s comic, got hijacked by 4chan around 2015, morphing from a stoner vibe to a symbol co-opted by alt-right groups, much to Furie’s dismay.

Memes thrive on remixing. A format—like Distracted Boyfriend or Drake Hotline Bling—gets born, then users slap new captions or contexts on it. X (Twitter) turbocharged this in the 2010s, with its fast pace and retweet mechanics. TikTok took it further with audio memes—think “Renegade” or “Oh No”—where a sound clip spawns endless video riffs. Reddit and Instagram polish memes for broader audiences, but 4chan’s raw, unfiltered edge often sets the spark.

The culture’s… layered. You’ve got normie memes (think Minions or Boomer humor) that flood Facebook, then edgier deep-fried memes—overprocessed, surreal images—popular with Gen Z on X or Discord. There’s a political angle too: memes weaponize ideas, from leftist “eat the rich” jabs to /pol/’s conspiracy-laden provocations. QAnon’s cryptic drops, for instance, memed their way into fringe consciousness via 4chan and 8kun.

It’s not just fun—memes signal identity. Posting a niche Wojak or GigaChad meme marks you as “in” with certain crowds. They’re also a coping mechanism—COVID spawned a wave of dark humor memes about lockdowns and doomscrolling. And they move fast: a meme’s lifespan might be a week before it’s “dead” or “cringe,” though classics like Trollface endure.

Anyway, before I get too off topic: 4chan as a site runs on a simple structure: users post images or text, others reply, and it’s all at least pseudo-anonymous unless someone chooses a tripcode (a rare, optional ID). No likes, no follows—just content and chaos. It’s been sold a couple times, most recently in 2015 to Hiroyuki Nishimura, the 2channel creator, but its core vibe hasn’t shifted much. Love it or hate it, 4chan’s influence on online culture is undeniable, even if it’s pretty much constantly a lightning rod for controversy.

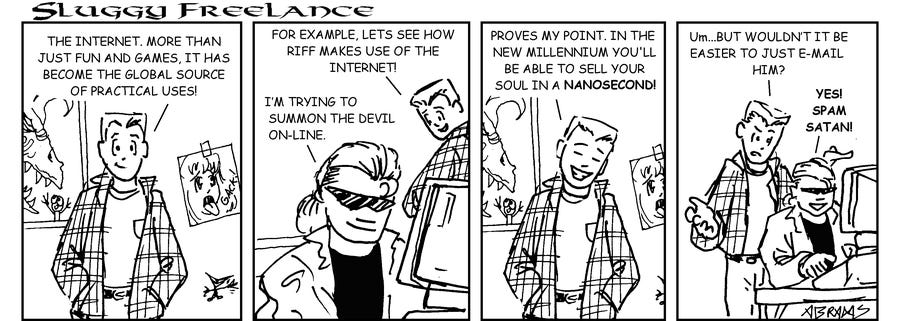

Oh, and back in the day, there were also a lot of webcomics.

Actually, that was the first ever Sluggy Freelance, but that pretty well sums it up.

This has become a somewhat lengthy piece already. Perhaps I’ll dive into webcomic paleontology another day. Look for something more cerebral for my next few articles.

Holy smokes, this is an expansive helping of internet nostalgia. Really well done.

Mushroom mushroom